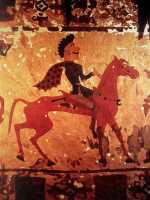

The Scythian | Scytha

SOURCE:

The Works of Lucian of Samosata. Translated by Fowler, H W and F G. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. 1905.

The seems to have been an oration or perhaps only part of one spoken by Lucian before a popular assembly at Athens probably before he became a well-known writer. As a foreigner, Lucian endeavours to recommend himself to the Athenians and to placate the public favor. The comparison he draws between Anacharsis and himself is ingenious. Lucian's artful address to the two leading men towards the end of the discourse shows his knowledge of mankind which we may suppose was of no little service to him.

1

Anacharsis was not the first Scythian who was induced by the love of Greek culture to leave his native country and visit Athens: he had been preceded by Toxaris, a man of high ability and noble sentiments, and an eager student of manners and customs; but of low origin, not like Anacharsis a member of the royal family or of the aristocracy of his country, but what they call ’an eight-hoof man,‘ a term which implies the possession of a waggon and two oxen. Toxaris never returned to Scythia, but died at Athens, where he presently came to be ranked among the Heroes; and sacrifice is still paid to ‘the Foreign Physician,’ as he was styled after his deification. Some account of the significance of this name, the origin of his worship, and his connexion with the sons of Asclepius, will not, I think, be out of place: for it will be seen from this that the Scythians, in conferring immortality on mortals, and sending them to keep company with Zamolxis, do not stand alone; since the Athenians permit themselves to make Gods of Scythians upon Greek soil.

2

At the time of the great plague, the wife of Architeles the Areopagite had a vision: the Scythian Toxaris stood over her and commanded her to tell the Athenians that the plague would cease if they would sprinkle their back-streets with wine. The Athenians attended to his instructions, and after several sprinklings had been performed, the plague troubled them no more; whether it was that the perfume of the wine neutralized certain noxious vapours, or that the hero, being a medical hero, had some other motive for his advice. However that may be, he continues to this day to draw a fee for his professional services, in the shape of a white horse, which is sacrificed on his tomb. This tomb was pointed out by Dimaenete as the place from which he issued with his instructions about the wine; and beneath it Toxaris was found buried, his identity being established not merely by the inscription, of which only a part remained legible, but also by the figure engraved on the monument, which was that of a Scythian, with a bow, ready strung, in his left hand, and in the right what appeared to be a book. You may still make out more than half the figure, with the bow and book complete: but the upper portion of the stone, including the face, has suffered from the ravages of time. It is situated not far from the Dipylus, on your left as you leave the Dipylus for the Academy. The mound is of no great size, and the pillar lies prostrate: yet it never lacks a garland, and there are statements to the effect that fever-patients have been known to be cured by the hero; which indeed is not surprising, considering that he once healed an entire city.

3

However, my reason for mentioning Toxaris was this. He was still alive, when Anacharsis landed at Piraeus and made his way up to Athens, in no small perturbation of spirit; a foreigner and a barbarian, everything was strange to him, and many things caused him uneasiness; he knew not what to do with himself; he saw that everyone was laughing at his attire; he could find no one to speak his native tongue;— in short he was heartily sick of his travels, and made up his mind that he would just see Athens, and then retreat to his ship without loss of time, get on board, and so back to the Bosphorus; once there he had no great journey to perform before he would be home again. In this frame of mind he had already reached the Ceramicus, when his good genius appeared to him in the guise of Toxaris. The attention of the latter was immediately arrested by the dress of his native country, nor was it likely that he would have any difficulty in recognizing Anacharsis, who was of noble birth and of the highest rank in Scythia. Anacharsis, on the other hand, could not be expected to see a compatriot in Toxaris, who was dressed in the Greek fashion, without sword or belt, wore no beard, and from his fluent speech might have been an Athenian born; so completely had time transformed him.

4

‘You are surely Anacharsis, the son of Daucetas?’ he said, addressing him in the Scythian language. Anacharsis wept tears of joy; he not only heard his mother-tongue, but heard it from one who had known him in Scythia. ‘How comes it, sir, that you know me?’ he asked. ‘I too am of that country; my name is Toxaris; but it is probably not known to you, for I am a man of no family.’

‘Are you that Toxaris,’ exclaimed the other, ‘of whom I heard that for love of Greece he had left wife and children in Scythia, and gone to Athens, and was there dwelling in high honour?’

5

‘What, is my name still remembered among you?— Yes, I am Toxaris.’

‘Then,’ said Anacharsis, ‘you see before you a disciple, who has caught your enthusiasm for Greece; it was with no other object than this that I set out on my travels. The hardships I have endured in the countries through which I passed on my way hither are infinite; and I had already decided, when I met you, that before the sun set I would return to my ship; so much was I disturbed at the strange and outlandish sights that I have seen. And now, Toxaris, I adjure you by Scimetar and Zamolxis, our country’s Gods,— take me by the hand, be my guide, and make me acquainted with all that is best in Athens and in the rest of Greece; their great men, their wise laws, their customs, their assemblies, their constitution, their everyday life. You and I have both travelled far to see these things: you will not suffer me to depart without seeing them?’

‘What! come to the very door, and then turn back? This is not the language of enthusiasm. However, there is no fear of that — you will not go back, Athens will not let you off so easily. She is not so much at a loss for charms wherewith to detain the stranger: she will take such a hold on you, that you will forget your own wife and children — if you have any. Now I will put you into the readiest way of seeing Athens, ay, and Greece, and the glories of Greece. There is a certain philosopher living here; he is an Athenian, but has travelled a great deal in Asia and Egypt, and held intercourse with the most eminent men. For the rest, he is none of your moneyed men: indeed, he is quite poor; be prepared for an old man, dressed as plainly as could be. Yet his virtue and wisdom are held in such esteem, that he was employed by them to draw up a constitution, and his ordinances form their rule of life. Make this man your friend, study him, and rest assured that in knowing him you know Greece; for he is an epitome of all that is excellent in the Greek character. I can do you no greater service than to introduce you to him.’

6

‘Let us lose no time, then, Toxaris. Take me to him. But perhaps that is not so easily done? He may slight your intercessions on my behalf?’

‘You know not what you say. Nothing gives him greater pleasure than to have an opportunity of showing his hospitality to strangers. Only follow me, and you shall see how courteous and benevolent he is, and how devout a worshipper of the God of Hospitality. But stay: how fortunate! here he comes towards us. See, he is wrapped in thought, and mutters to himself. — Solon!’ he cried; ‘I bring you the best of gifts — a stranger who craves your friendship.

7

He is a Scythian of noble family; but has left all and come here to enjoy the society of Greeks, and to view the wonders of their country. I have hit upon a simple expedient which will enable him to do both, to see all that is to be seen, and to form the most desirable acquaintances: in other words, I have brought him to Solon, who, if I know anything of his character, will not refuse to take him under his protection, and to make him a Greek among Greeks.— It is as I told you, Anacharsis: having seen Solon, you have seen all; behold Athens; behold Greece. You are a stranger no longer: all men know you, all men are your friends; this it is to possess the friendship of the venerable Solon. Conversing with him, you will forget Scythia and all that is in it. Your toils are rewarded, your desire is fulfilled. In him you have the mainspring of Greek civilization, in him the ideals of Athenian philosophers are realized. Happy man — if you know your happiness — to be the friend and intimate of Solon!’

8

It would take too long to describe the pleasure of Solon at Toxaris’s ‘gift,’ his words on the occasion, and his subsequent intercourse with Anacharsis — how he gave him the most valuable instruction, procured him the friendship of all Athens, showed him the sights of Greece, and took every trouble to make his stay in the country a pleasant one; and how Anacharsis for his part regarded the sage with such reverence, that he was never willingly absent from his side. Suffice it to say, that the promise of Toxaris was fulfilled: thanks to Solon’s good offices, Anacharsis speedily became familiar with Greece and with Greek society, in which he was treated with the consideration due to one who came thus strongly recommended; for here too Solon was a lawgiver: those whom he esteemed were loved and admired by all. Finally, if we may believe the statement of Theoxenus, Anacharsis was presented with the freedom of the city, and initiated into the mysteries; nor does it seem likely that he would ever have returned to Scythia, had not Solon died.

9

And now perhaps I had better put the moral to my tale, if it is not to wander about in a headless condition. What are Anacharsis and Toxaris doing here today in Macedonia, bringing Solon with them too, poor old gentleman, all the way from Athens? It is time for me to explain. The fact is, my situation is pretty much that of Anacharsis. I crave your indulgence, in venturing to compare myself with royalty. Anacharsis, after all, was a barbarian; and I should hope that we Syrians are as good as Scythians. And I am not comparing myself with Anacharsis the king, but Anacharsis the barbarian. When first I set foot in your city, I was filled with amazement at its size, its beauty, its population, its resources and splendour generally. For a time I was dumb with admiration; the sight was too much for me. I felt like the island lad Telemachus, in the palace of Menelaus; and well I might, as I viewed this city in all her pride;

A garden she, whose flowers are ev’ry blessing.

10

Thus affected, I had to bethink me what course I should adopt. For as to lecturing here, my mind had long been made up about that; what other audience could I have in view, that I should pass by this great city in silence? To make a clean breast of it, then, I set about inquiring who were your great men; for it was my design to approach them, and secure their patronage and support in facing the public. Unlike Anacharsis, who had but one informant, and a barbarian at that, I had many; and all told me the same tale, in almost the same words. ‘Sir,’ they said, ‘we have many excellent and able men in this city — nowhere will you find more: but two there are who stand preeminent; who in birth and in prestige are without a rival, and in learning and eloquence might be matched with the Ten Orators of Athens. They are regarded by the public with feelings of absolute devotion: their will is law; for they will nothing but the highest interests of the city. Their courtesy, their hospitality towards strangers, their unassuming benevolence, their modesty in the midst of greatness, their gentleness, their affability,— all these you will presently experience, and will have something to say on the subject yourself. But — wonder of wonders!— these two are of one house, father and son.

11

For the father, conceive to yourself a Solon, a Pericles, an Aristides: as to the son, his manly comeliness and noble stature will attract you at the first glance; and if he do but say two words, your ears will be taken captive by the charm that sits upon his tongue. When he speaks in public, the city listens like one man, open-mouthed; ’tis Athens listening to Alcibiades; yet the Athenians presently repented of their infatuation for the son of Clinias, but here love grows to reverence; the welfare of this city, the happiness of her citizens, are all bound up in one man. Once let the father and son admit you to their friendship, and the city is yours; they have but to raise a finger, to put your success beyond a doubt.’— Such, by Heaven (if Heaven must be invoked for the purpose), such was the unvarying report I heard; and I now know from experience that it fell far short of the truth. Then up, nor waste thy days In indolent delays,

as the Cean poet cries; I must strain every nerve, work body and soul, to gain these friends. That once achieved, fair weather and calm seas are before me, and my haven is near at hand.