Table of Contents

<html>

<a href=“http://lucianofsamosata.info/wiki/doku.php?id=submission_page”><img src=“http://lucianofsamosata.info/images/contact.png” /></a>

</html>

Buy the book, only $1.00 (ebook) or $6.50 (paperback)

Cyrenaics Handbook - - eBook from Amazon $1.00

Cyrenaics Handbook - - Paperback from Amazon $6.50

Cyrenaics Handbook - - eBook from Scribd $1.00

The Cyrenaics Resource

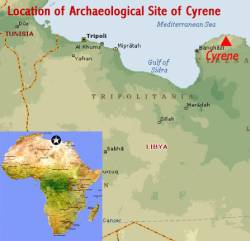

The Cyrenaic school of philosophy, named from the city of Cyrene where the movement was founded, expanded in influence from about 400 BC to 300 BC and thereafter quickly dissipated. The Cyrenaics believe that Hedonism is the source of happiness and that pleasure is the chief good at which all things are intended. It is common wisdom that there are two main sources for Cyrenaism, namely Socrates and the sophists, in particular Protagoras. The ethical doctrines of the school are derived from Socrates' doctrine of the Chief Good. The Cyrenaics accepted this imperative but instead of fulfilling it through Virtue they choose to fulfill the Chief Good through a doctrine of pleasure. The supremacy of pleasure is to what all things aim. The epistemological foundations of Cyrenaism are derived from the skeptical views of Protagoras. The idea that knowledge is relative is prominent in Cyrenaic thought and is used to justify their hedonistic ethical doctrines.

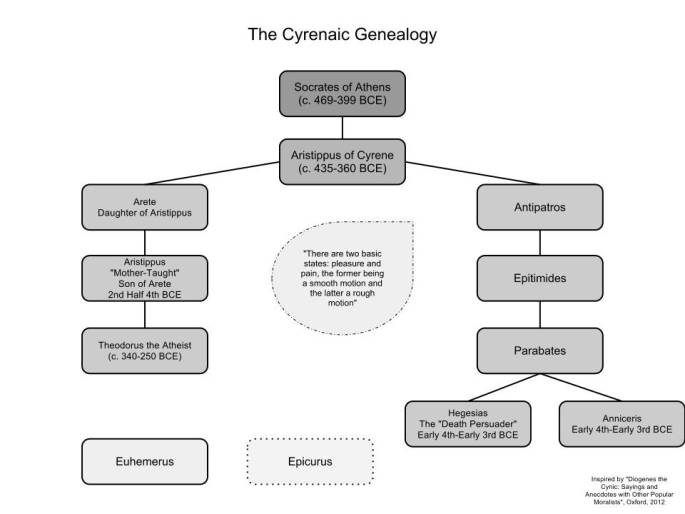

Aristippus of Cyrene, ca. 400 BC, is considered to be the founder of the school. While it is unclear how much of later Cyrenaic doctrine is derived from his life and writings, he does provide a crucial link to Socrates who is considered the founder of many other schools of thought in Ancient Greece and it lends credibility and authority to the Cyrenaic endeavor. Through Aristippus, the school spread, on one hand through his daughter Arete - Aristippus the Younger - Theodorus the Atheist, and on the other, from Antipatros – Epitimides – Parabates – Hegesias & Anniceris. The exact details of each individual's significance and position are outlined throughout this compilation.

The Cyrenaics began their philosophical inquiry by agreeing with Protagoras that all knowledge is relative. On a very basic level, the elemental senses can determine what is true but things do not have meaning or significance in-and-of-themselves. From this premise, the Cyrenaics concluded that we can only understand our feelings or the impressions of what things produce upon us. When this insight is put to practical use, it is determined that happiness can only be obtained through pleasurable sensations (since they are real) and the avoidance of painful situations. Bodily pleasures are more intense than mental image-based pleasures. Likewise, physical pain is more intense than mental anguish. Pleasure, therefore, is the path to happiness. The measure of a good individual is if he or she can maximize their pleasure and minimize their pain. Unlike the doctrine of the Cynics, Virtue is a not a shortcut to happiness; Virtue is a means to obtain more pleasure. It is not the end.

Many of the figures of the Cyrenaics subscribed to the ideas originally laid out by Aristippus and his immediate followers but also had other interests in using Cyrenaic doctrine. Theodorus took the doctrine to the extreme and was known as the atheist for his heterodox views on the divine. Euhemerus, although not normally grouped with the Cyrenaics, used their doctrine to develop a unique idea on how the divine mythology was formed from human, historical characters. Hegesias determined that life may not be worth living and became so influential being a “Death Persuader” he had to be silenced for the public good.

Over time, however, the Cyrenaic doctrine dissolved. The base sensist approach to happiness eroded over time. The pleasure doctrine shifted to reduce pleasure to a mere negative state where painlessness is considered to be the route to happiness. Others considered pleasure to be mere “cheerfulness and indifference”. The parallels to the Epicurean ideal position of emotional calm (sagicity) are manifest. Cyrenaism was loosely governed and a spectrum of what constitutes pleasure existed. As expectations of doctrine building took the place of Socratic questioning in philosophy, Cyreniacs failed to live up to the common expectations; their doctrines became a set of maxims for living rather than a solid philosophical school with systematic ideas. Because of the unraveling of Cyrenaic principles, it is assumed that the school eventually merged into Epicureanism which housed a more robust and systematic form of hedonism.

Modeled from this source: Turner, William. “Cyrenaic School of Philosophy.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 15 Nov. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04591a.htm>.

Editor Notes

This handbook contains the lives, writings, and doctrines of the Cyrenaic school by compiling the primary sources of the material. This handbook is not a summary or analysis of the Cyrenaic school. This handbook provides all of the (open and available) references to the Cyrenaic school within the ancient texts. Its main function is to put together in one place all of the references into one book. It is designed for the scholar and for the student. The scholar can use this resource to save time by having everything ready in one place. All references are taken from copyright-expired texts or open source (free) texts from places like Gutenberg and Archive.org. No copyrighted material is used in this book. All endnotes point to the source of each reference. The student of ancient philosophy will find this to be an aid to your understanding of the Cyrenaic school and may even influence your thinking. Many will undoubtedly use this book to aide their understanding of Hellenic Philosophy and Epicureanism.

Compiled, annotated, and edited by Frank Redmond.

- Frank Redmond – 2012 (1st Edition; 1.0)

- Frank Redmond – 2015 (2nd Edition; 2.0)

- Frank Redmond – 2016 (2nd Edition; 2.2)

- 2nd Edition (2015) modifications – Fixed minor content bugs; corrected citations; added and replaced textual content.

- 2nd Edition (2016) modifications – Changed style; standardized citations.

Cyrenaic Resources (Primary)

Inspired by Diogenes the Cynic: Sayings and Anecdotes with Other Popular Moralists, Oxford World Classics, 2012

Aristippus: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology

<blockquote>Aristippus, son of Aritades, born at Cyrene, and founder of the Cyrenaic School of Philosophy, came over to Greece to be present at the Olympic games, where he fell in with Ischomachus the agriculturist (whose praises are the subject of Xenophon's Oeconomicus), and by his description was filled with so ardent a desire to see Socrates, that he went to Athens for the purpose (Plut. de Curios. 2), and remained with him almost up to the time of his execution, 399 BC. Diodorus (xv. 76) gives 366 BC as the date of Aristippus, which agrees very well with the facts which we know about him, and with the statement (Schol. ad Aristopli. Plut. 179), that Lais, the courtesan with whom he was intimate, was born 421 BC.

Though a disciple of Socrates, he wandered both in principle and practice very far from the teaching and example of his great master. He was luxurious in his mode of living; he indulged in sensual gratifications, and the society of the notorious Lais; he took money for his teaching being the first of the disciples of Socrates who did so (Diog. Laert. ii. 65), and avowed to his instructor that he resided in a foreign land in order to escape the trouble of mixing in the politics of his native city. (Xen. Mem. ii. 1.) He passed part of his life at the court of Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, and is also said to have been taken prisoner by Artaphernes, the satrap who drove the Spartans from Rhodes 396 BC. (Diod. Sic. xiv. 79) He appears, however, at last to have returned to Cyrene, and there he spent his old age. The anecdotes which are told of him, and of which we find a most tedious number in Diogenes Laertius (ii. 65, &c.), by no means give us the notion of a person who was the mere slave of his passions, but rather of one who took a pride in extracting enjoyment from all circumstances of every kind, and in controlling adversity and prosperity alike. They illustrate and confirm the two statements of Horace (Ep. i. 1. 18), that to observe the precepts of Aristippus is “milii res, non me rebus subjungere” and (i. 17. 23) that, “omnis Aristippum decuit color et status et res.” Thus when reproached for his love of bodily indulgences, he answered, that there was no shame in enjoying them, but that it would be disgraceful if he could not at any time give them up. When Dionysius, provoked at some of his remarks, ordered him to take the lowest place at table, he said, ”You wish to dignify the seat.” Whether he was prisoner to a satrap, or grossly insulted and even spit upon by a tyrant, or enjoying the pleasures of a banquet, or reviled for faithlessness to Socrates by his fellow-pupils, he maintained the same calm temper. To Xenophon and Plato he was very obnoxious, as we see from the Memorabilia (I. c.), where he maintains an odious discussion against Socrates in defence of voluptuous enjoyment, and from the Phaedo (p. 59, c), where his absence at the death of Socrates, though he was only at Aegina, 200 stadia from Athens, is doubtless mentioned as a reproach. Aristotle, too, calls him a sophist (Metaphys. ii. 2), and notices a story of Plato speaking to him. With rather undue vehemence, and of his replying with calmness (Rhet. ii. 23.) He imparted his doctrine to his daughter Arete, by whom it was communicated to her son, the younger Aristippus (hence called Mother-Taught), and by him it is said to have been reduced to a system. Laertius, on the authority of Sotion (205 BC) and Panaetius (143 BC), gives a long list of books whose authorship is ascribed to Aristippus, though he also says that Sosicrates of Rhodes (255 BC) states, that he wrote nothing. Among these are treatises “Concerning Education”, “Concerning Virtue”, “Concerning Fortune”, and many others. Some epistles attributed to him are deservedly rejected as forgeries. One of these is to Arete, and its spuriousness is proved, among other arguments, by the occurrence in it of the name of a city near Cyrene, Berenike, which must have been given by the Macedonians, in whose dialect Beta stands for Phi, so that the name is equivalent to Pherenike, the victorious.

Source: Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Boston: Little, Brown, 1867. Internet resource.</blockquote>

Satirical and Poetical Interpretation of Aristippus

Lucian, Sale of Creeds 12

<blockquote>Zeus. Now for the Cyrenaic, the crowned and purple-robed.

Her. Attend please, gentlemen all. A most valuable article, this, and calls for a long purse. Look at him. A sweet thing in creeds. A creed for a king. Has any gentleman a use for the Lap of Luxury? Who bids?

Third D. Come and tell me what you know. If you are a practical creed, I will have you.

Her. Please not to worry him with questions, sir. He is drunk, and cannot answer; his tongue plays him tricks, as you see.

Third D. And who in his senses would buy such an abandoned reprobate? How he smells of scent! And how he slips and staggers about! Well, you must speak for him, Hermes. What can he do? What is his line?

Her. Well, for any gentleman who is not strait-laced, who loves a pretty girl, a bottle, and a jolly companion, he is the very thing. He is also a past master in gastronomy, and a connoisseur in voluptuousness generally. He was educated at Athens, and has served royalty in Sicily, where he had a very good character. Here are his principles in a nutshell: Think the worst of things: make the most of things: get all possible pleasure out of things.

Third D. You must look for wealthier purchasers. My purse is not equal to such a festive creed.

Her. Zeus, this lot seems likely to remain on our hands.

Source: Lucian of Samosata Project</blockquote>

Horace, Satire 2.3.82-110

<blockquote>

The Madness of Avarice

“Avarice should get the largest dose of medicine,

I’d say: all of Anticyra’s hellebore for the mad.

Staberius’ heirs had to carve his wealth on his tomb,

If not they’d to entertain the masses with a hundred

Paired gladiators, at a funeral feast, to be planned

By Arrius, plus all of Africa’s corn. His will said:

‘Whether I’m right or wrong in this, don’t criticise me.’

That’s what Staberius’ proud mind foresaw, I think.

‘So what did he mean when he willed that his heirs

Should carve his wealth in stone?’ Well, he thought poverty

Was a mighty evil, all his life, and guarded against it

Strongly, so if he’d chanced to die a penny poorer,

He’d have thought that much less of himself: he thought all things,

Virtue, reputation, honour, things human or divine

Bowed to the glory of riches: that he who’s garnered them

Is famous, just and brave. ‘And wise?’ Of course, a king,

Whatever he wishes. He hoped that wealth, won as if by

Virtue, would bring him great fame. Where’s the difference

Between him and Aristippus the Greek, who in deepest

Libya, ordered his slaves who travelled more slowly

Under its weight, to unload his gold? Which was crazier?

Useless examples explain one mystery by another.

If a man bought lutes, and piled them up together,

While caring not a fig for the lute or any art:

Or, though no cobbler, bought lasts and awls: or hating trade

Ships’ sails, all would think him insane and obsessed

And they’d be right. Why is the man who hoards gold

And silver any different from them? He’s no idea

How to use his pile, fearing to touch it as sacred.”

Source: Horace, Satires.

Translated by A. S. Kline © 2005 All Rights Reserved</blockquote>

Horace, Epistles 1.1.1-19

<blockquote>

An end to verse

You, Maecenas, of whom my first Muse told, of whom my

Last shall tell, seek to trap me in the old game again,

Though I’m proven enough, and I’ve won my discharge.

My age, spirit are not what they were. Veianius

Hangs his weapons on Hercules’ door, stops pleading to

The crowd for his life, from the sand, by hiding himself

In the country. A voice always rings clear in my ear:

‘While you’ve time, be wise, turn loose the ageing horse,

Lest he stumbles, broken winded, jeered, at the end.’

So now I’m setting aside my verse, and other tricks:

My quest and care is what’s right and true, I’m absorbed

In it wholly: I gather, then store for later use.

In case you ask who’s my master, what roof protects me,

I’m not bound to swear by anyone’s precepts,

I’m carried, a guest, wherever the storm-wind blows me.

Now I seek action, and plunge in the civic tide,

The guardian, and stern attendant of true virtue:

Now I slip back privately to Aristippus’ precepts,

Trying to bend world to self, and not self to world.

Source: Horace, Epistles.

Translated by A. S. Kline © 2005 All Rights Reserved</blockquote>

Horace, Epistles 1.17.1-32

<blockquote>Humble Advice

Though you attend well enough to your own interests,

Scaeva, and know too how to behave with the great,

Hear the views of a dear friend, who’s still learning:

As if a blind man wished to show you the way: but see

If I’ve anything to say that you might care to own to.

If you love dearest peace, and to sleep till daybreak,

If dust, the sound of wheels, and tavern-life offend you,

I’ll order you off to silent Ferentinum:

Enjoyment’s not for the rich alone: he’s not lived

Badly, who’s escaped attention from birth to death.

But if you want to help your friends and help yourself

A little more, the hungry man head’s for the feast.

‘If Aristippus was happy to eat vegetables,

He wouldn’t woo princes.’ ‘If he knew how to woo

Princes, my critic would scorn vegetables.’ Which

Words and example do you approve? Tell me, or since

You’re younger, here’s why Aristippus is wiser.

This is the way, they say, he parried the fierce Cynic:

‘You play the fool for the people, I for myself:

It’s nobler and truer. I serve so a horse bears me,

A prince feeds me: you beg for scraps, but are still less

Than the giver, though you boast of needing no man.’

All styles, states, circumstances suited Aristippus

Aiming higher, but mostly content with what he had.

But I’d be amazed if a change in his way of life,

Would suit one austerity clothes in a Cynic’s rags.

The first won’t wait for a purple robe, he’ll walk

Through the crowded streets wearing anything he has,

And play either role without any awkwardness:

The second will shun a fine cloak made in Miletus,

As he would a dog or snake, and die of cold if you

Don’t return his rags. Do so, and let him be a fool.

Source: Horace, Epistles.

Translated by A. S. Kline © 2005 All Rights Reserved</blockquote>

Aristippus in the Suda

Suda, Alpha 3908

<blockquote>Son of Aritades, from Cyrene, a philosopher, a pupil of Socrates; by whom the sect called Cyrenaic began. He was the first of the Socratics to take wages. He was on bad terms with Xenophon, and he was able to adapt himself to both time and place. And he enjoyed what things were at hand and pursued pleasure, but he did not by toil chase after the enjoyment of things which he did not have. Hence Diogenes called him the “king's dog”. His sayings [were] the best and greatest. His daughter Arete learned [from him], whose [student was] her son the young Aristippos, who was named Mother-taught, and his [student was] Theodoros, who was called “Godless”, then “God”; and his [student was] Antipater, and his [student was] Epitimedes of Cyrene, his Paraibates, his Hegesias the Advocate of Death [by suicide], and his Annikeris, who ransomed Plato.

Source: Suda On Line and the Stoa Consortium</blockquote>

Suda, Alpha 3909

<blockquote>Companion of Socrates, who was charming and took pleasure in all things. It is said that when his child was carrying money and was burdened by the weight he said, “Then cast off what's weighing you down.” When he was being plotted against on a voyage he cast into the sea the things on account of which he was being conveyed. “For,” he said, “the loss is my salvation.” And he always ribbed Antisthenes for his dourness. And he came to Dionysius the tyrant of Sicily and won the drinking and led the dance for the others and put on purple clothes. But Plato, when the robe was brought to him, said some iambics of Euripides: “I would not put on feminine clothes, having been born male, and from a male line.” Aristippos took it and said with a laugh [some lines] of the same poet: “for the moderate mind will not be corrupted in Bacchic revelries.” Making a request on behalf of a friend and not obtaining it, he fell down to his [Dionysius'] feet and won him over: “I am not responsible for this flattery,” he said, “but Dionysius, who has ears in his knees.”

Source: Suda On Line and the Stoa Consortium</blockquote>

Aristippus: Synopsis

Diogenes Laertius, 2.65-66, 2.83-85

<blockquote>65. Aristippus was by birth a citizen of Cyrene and, as Aeschines informs us, was drawn to Athens by the fame of Socrates. Having come forward as a lecturer or sophist, as Phanias of Eresus, the Peripatetic, informs us, he was the first of the followers of Socrates to charge fees and to send money to his master. And on one occasion the sum of twenty minae which he had sent was returned to him, Socrates declaring that the supernatural sign would not let him take it; the very offer, in fact, annoyed him. Xenophon was no friend to Aristippus; and for this reason he has made Socrates direct against Aristippus the discourse in which he denounces pleasure. Not but what Theodorus in his work On Sects abuses him, and so does Plato in the dialogue On the Soul, as has been shown elsewhere.

66. He was capable of adapting himself to place, time and person, and of playing his part appropriately under whatever circumstances. Hence he found more favour than anybody else with Dionysius, because he could always turn the situation to good account. He derived pleasure from what was present, and did not toil to procure the enjoyment of something not present. Hence Diogenes called him the king's poodle Timon, too, sneered at him for luxury in these words:

Such was the delicate nature of Aristippus, who groped after error by touch.

He is said to have ordered a partridge to be bought at a cost of fifty drachmae, and, when someone censured him, he inquired, “Would not you have given an obol for it?” and, being answered in the affirmative, rejoined, “Fifty drachmae are no more to me.”

[…]

83. There have been four men called Aristippus, (1) our present subject, (2) the author of a book about Arcadia, (3) the grandchild by a daughter of the first Aristippus, who was known as his mother's pupil, (4) a philosopher of the New Academy.

The following books by the Cyrenaic philosopher are in circulation: a history of Libya in three Books, sent to Dionysius; one work containing twenty-five dialogues, some written in Attic, some in Doric, as follows:

84. Artabazus. To the shipwrecked. To the Exiles. To a Beggar. To Laïs. To Porus. To Laïs, On the Mirror. Hermias. A Dream. To the Master of the Revels. Philomelus. To his Friends. To those who blame him for his love of old wine and of women. To those who blame him for extravagant living. Letter to his daughter Arete. To one in training for Olympia. An Interrogatory. Another Interrogatory. An Occasional Piece to Dionysius. Another, On the Statue. Another, On the daughter of Dionysius. To one who considered himself slighted. To one who essayed to be a counsellor.

Some also maintain that he wrote six Books of Essays; others, and among them Sosicrates of Rhodes, that he wrote none at all.

85. According to Sotion in his second book, and Panaetius, the following treatises are his:

On Education. On Virtue. Introduction to Philosophy. Artabazus. The Ship-wrecked. The Exiles. Six books of Essays. Three books of Occasional Writings. To Laïs. To Porus. To Socrates. On Fortune.

He laid down as the end the smooth motion resulting in sensation.

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925

</blockquote>

Aelian, Various Histories Book 14.6

<blockquote>Aristippus his opinion concerning chearfulness. Aristippus by strong arguments advised that we should not be anxious about things past or future; arguing, that not to be troubled at such things, is a sign of a constant clear spirit. He also advised to take care only for the present day, and in that day, only of the present part, wherein something was done or thought; for he said, the present only is in our power, not the past or future; the one being gone, the other uncertain whether ever it will come.

Source: Aelian. His Various History (Varia Historia).

Thomas Stanley, translator (1665)</blockquote>

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae Book 12

<blockquote>We find also whole schools of philosophers which have openly professed to have made choice of pleasure. And there is the school called the Cyrenaic, which derives its origin from Aristippus the pupil of Socrates: and he devoted himself to pleasure in such a way, that he said that it was the main end of life; and that happiness was founded on it, and that happiness was at best but short-lived. And he, like the most debauched of men, thought that he had nothing to do either with the recollection of past enjoyments, or with the hope of future ones; but he judged of all good by the present alone, and thought that having enjoyed, and being about to enjoy, did not at all concern him; since the one case had no longer any existence, and the other did not yet exist and was necessarily uncertain: acting in this respect like thoroughly dissolute men, who are content with being prosperous at the present moment. And his life was quite consistent with his theory; for he spent the whole of it in all kinds of luxury and extravagance, both in perfumes, and dress, and women. Accordingly, he openly kept Lais as his mistress; and he delighted in all the extravagance of Dionysius, although he was often treated insultingly by him.

Source: Athenaeus, Deipnosophists.

Translated by C. D. Yonge, 1854</blockquote>

Eusebius, Preparation for the Gospel 14.18

<blockquote>Now Aristippus was a companion of Socrates, and was the founder of the so-called Cyrenaic sect, from which Epicurus has taken occasion for his exposition of man's proper end. Aristippus was extremely luxurious in his mode of life, and fond of pleasure; he did not, however, openly discourse on the end, but virtually used to say that the substance of happiness lay in pleasures. For by always making pleasure the subject of his discourses he led those who attended him to suspect him of meaning that to live pleasantly was the end of man.

Source: Eusebius of Caesarea: Praeparatio Evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel).

Tr. E.H. Gifford (1903)</blockquote>

Socratic Aristippus

Aristotle, Rhetoric 2.23.11

<blockquote>Or again as Aristippus said in reply to Plato when he spoke somewhat too dogmatically, as Aristippus thought: 'Well, anyhow, our friend', meaning Socrates, 'never spoke like that'.

Source: Rhetoric by Aristotle: Translated by W. Rhys Roberts </blockquote>

Plutarch, On Curiosity 2

<blockquote> And Aristippus, meeting Ischomachus at the Olympic games, asked him what those notions were with which Socrates had so powerfully charmed the minds of his young scholars; upon the slight information whereof, he was so passionately inflamed with a desire of going to Athens, that he grew pale and lean, and almost languished till he came to drink of the fountain itself, and had been acquainted with the person of Socrates, and more fully learned that philosophy of his, the design of which was to teach men how to discover their own ills and apply proper remedies to them.

Source: Plutarch's Morals, Translated by William W. Goodwin Ph.D. (1874)</blockquote>

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.68,71,72,74,76,79,80

<blockquote>68. Being asked what he had gained from philosophy, he replied, “The ability to feel at ease in any society.” […] Being once asked what advantage philosophers have, he replied, “Should all laws be repealed, we shall go on living as we do now.”

71. An advocate, having pleaded for him and won the case, thereupon put the question, “What good did Socrates do you?” “Thus much,” was the reply, “that what you said of me in your speech was true.”

72. When he was reproached for employing a rhetorician to conduct his case, he made reply, “Well, if I give a dinner, I hire a cook.”

74. To the accusation that, although he was a pupil of Socrates, he took fees, his rejoinder was, “Most certainly I do, for Socrates, too, when certain people sent him corn and wine, used to take a little and return all the rest; and he had the foremost men in Athens for his stewards, whereas mine is my slave Eutychides.”

76. Being asked how Socrates died, he answered, “As I would wish to die myself.”

79. He was once staying in Asia and was taken prisoner by Artaphernes, the satrap. “Can you be cheerful under these circumstances?” some one asked. “Yes, you simpleton,” was the reply, “for when should I be more cheerful than now that I am about to converse with Artaphernes [having learned that from Socrates]?”

80. To the critic who censured him for leaving Socrates to go to Dionysius, his rejoinder was, “Yes, but I came to Socrates for education and to Dionysius for recreation.” When he had made some money by teaching, Socrates asked him, “Where did you get so much?” to which he replied, “Where you got so little.”

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925</blockquote>

Aristippus: Opulence

Athenaeus, Book 8

<blockquote>Why, even Aristippus the Socratic was a fish-eater, and when reproached on one occasion by Plato for his love of dainties, as Sotion and Hegesander say — but here is what the Delphian writes: 'When Plato criticized Aristippus for buying so many fish, he replied that he had bought them for only fourpence. To this Plato said that he would have bought them himself at that price, whereupon Aristippus said: “You see, Plato! It isn't I who am a fish-lover, but you who are a money-lover.”

Source: Athenaeus. Loeb Classical Library.

Harvard University Press, 1927 thru 1941.

Translation by Charles Burton Gulick. </blockquote>

Seneca, On Benefits 7.25

<blockquote>Aristippus once, when enjoying a perfume, said: “Bad luck to those effeminate persons who have brought so nice a thing into disrepute.”

Source: L. Annaeus Seneca, On Benefits

By Seneca, Edited by Aubrey Stewart

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3794/3794-h/3794-h.htm#2H_4_0009</blockquote>

Clement of Alexandria, Pedogogy 2.8

<blockquote>I know, too, the words of Aristippus the Cyrenian. Aristippus was a luxurious man. He asked an answer to a sophistical proposition in the following terms: “A horse anointed with ointment is not injured in his excellence as a horse, nor is a dog which has been anointed, in his excellence as a dog; no more is a man,” he added, and so finished

Source: Clement. Translated by Thomas Smith.

From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 8. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886.)

Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/02092.htm</blockquote>

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.66,68,75,76,77

<blockquote>66. He is said to have ordered a partridge to be bought at a cost of fifty drachmae, and, when someone censured him, he inquired, “Would not you have given an obol for it?” and, being answered in the affirmative, rejoined, “Fifty drachmae are no more to me.”

68. Being reproached for his extravagance, he said, “If it were wrong to be extravagant, it would not be in vogue at the festivals of the gods.”

75. To one who reproached him with extravagance in catering, he replied, “Wouldn't you have bought this if you could have got it for three obols?” The answer being in the affirmative, “Very well, then,” said Aristippus, “I am no longer a lover of pleasure, it is you who are a lover of money.”

76. When Charondas (or, as others say, Phaedo) inquired, “Who is this who reeks with unguents?” he replied, “It is I, unlucky wight, and the still more unlucky Persian king. But, as none of the other animals are at any disadvantage on that account, consider whether it be not the same with man. Confound the effeminates who spoil for us the use of good perfume.”

76-77. Polyxenus the sophist once paid him a visit and, after having seen ladies present and expensive entertainment, reproached him with it later. After an interval Aristippus asked him, “Can you join us today?”. On the other accepting the invitation, Aristippus inquired, “Why, then, did you find fault? For you appear to blame the cost and not the entertainment.”

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925 </blockquote>

Aristippus: Examining Wealth and Fortune

Vitruvius, On Architecture 6.1.1-2

<blockquote>1.1 It is related of the Socratic philosopher Aristippus that, being shipwrecked and cast ashore on the coast of the Rhodians, he observed geometrical figures drawn thereon, and cried out to his companions: “Let us be of good cheer, for I seethe traces of man.” With that he made for the city of Rhodes, and went straight to the gymnasium. There he fell to discussing philosophical subjects, and presents were bestowed upon him, so that he could not only fit himself out, but could also provide those who accompanied him with clothing and all other necessaries of life. When his companions wished to return to their country, and asked him what message he wished them to carry home, he bade them say this: that children ought to be provided with property and resources of a kind that could swim with them even out of a shipwreck.

1.2 These are indeed the true supports of life, and neither Fortune's adverse gale, nor political revolution, nor ravages of war can do them any harm. Developing the same idea, Theophrastus, urging men to acquire learning rather than to put their trust in money, states the case thus: “The man of learning is the only person in the world who is neither a stranger when in a foreign land, nor friendless when he has lost his intimates and relatives; on the contrary, he is a citizen of every country, and can fearlessly look down upon the troublesome accidents of fortune. But he who thinks himself entrenched in defences not of learning but of luck, moves in slippery paths, struggling through life unsteadily and insecurely.”

Source: Vitruvius Pollio, The Ten Books on Architecture

Morris Hicky Morgan, Ed.

Harvard University Press: 1914</blockquote>

Plutarch, On the Fortune or Virtue of Alexander the Great

<blockquote>It is a strange thing; we applaud Socratic Aristippus, because, being sometimes clad in a poor threadbare cloak, sometimes in a Milesian robe, he kept a decency in both.

Source: Plutarch's Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands.

Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878).</blockquote>

Plutarch, On Tranquility of Mind

<blockquote>For most men leave the pleasant and delectable things behind them, and run with haste to embrace those which are not only difficult but intolerable. Aristippus was not of this number, for he knew, even to the niceness of a grain, to put prosperous against adverse fortune into the scale, that the one might outweigh the other. Therefore when he lost a noble farm, he asked one of his dissembled friends, who pretended to be sorry, not only with regret but impatience, for his mishap: “[You have] but one piece of land, but have I not three farms yet remaining?” He assenting to the truth of it: “Why then, [he said], should I not rather lament your misfortune, since it is the raving only of a mad man to be concerned at what is lost, and not rather rejoice in what is left?”

English Modernized

Source: Plutarch's Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands.

Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878).</blockquote>

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.67,63,77

<blockquote>67. Hence the remark of Strato, or by some accounts of Plato, “You alone are endowed with the gift to flaunt in robes or go in rags.”

73. Being asked on one occasion what is the difference between the wise man and the unwise, “Strip them both,” said he, “and send them among strangers and you will know.”

77. When his servant was carrying money and found the load too heavy – the story is told by Bion in his Lectures – Aristippus cried, “Pour away the greater part, and carry no more than you can manage.” […] Being once on a voyage, as soon as he discovered the vessel to be manned by pirates, he took out his money and began to count it, and then, as if by inadvertence, he let the money fall into the sea, and naturally broke out into lamentation. Another version of the story attributes to him the further remark that it was better for the money to perish on account of Aristippus than for Aristippus to perish on account of the money.

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925 </blockquote>

Aristippus: Examining Sexuality

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae Book 13

<blockquote>But Lais was so beautiful, that painters used to come to her to copy her bosom and her breasts. And Lais was a rival of Phryne, and had an immense number of lovers, never caring whether they were rich or poor, and never treating them with any insolence. And Aristippus every year used to spend whole days with her in Aegina, at the festival of Poseidon. And once, being reproached by his servant, who said to him, “You give her such large sums of money, but she admits Diogenes the Cynic for nothing”. He answered, “I give Lais a great deal, that I myself may enjoy her, and not that no one else may.” And when Diogenes said, “Since you, Aristippus, cohabit with a common prostitute, either, therefore, become a Cynic yourself, as I am, or else abandon her”. Aristippus answered him, “Does it appear to you, Diogenes, an absurd thing to live in a house where other men have lived before you?” “Not at all,” said he. “Well, then, does it appear to you absurd to sail in a ship in which other men have sailed before you?” “By no means,” said he. “Well, then,” replied Aristippus, “it is not a bit more absurd to be in love with a woman with whom many men have been in love already.”

Source: Athenaeus, Deipnosophists.

Translated by C. D. Yonge, 1854</blockquote>

Plutarch, On Love

<blockquote>As Aristippus testified to one that would have put him out of conceit with Lais, for that, as he said, she did not truly love him; no more, said he, am I beloved by pure wine or good fish, and yet I willingly make use of both.

Source: Plutarch's Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands.

Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878).</blockquote>

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.67,69,74,75

<blockquote>67. And when Dionysius gave him his choice of three courtesans, he carried off all three, saying, “Paris paid dearly for giving the preference to one out of three.” And when he had brought them as far as the porch, he let them go.

69. One day, as he entered the house of a courtesan, one of the lads with him blushed, whereupon he remarked, “It is not going in that is dangerous, but being unable to go out.”

74. To one who accused him of living with a courtesan, he put the question, “Why, is there any difference between taking a house in which many people have lived before and taking one in which nobody has ever lived?” The answer being “No,” he continued, “Or again, between sailing in a ship in which ten thousand persons have sailed before and in one in which nobody has ever sailed?” “There is no difference.” “Then it makes no difference,” said he, “whether the woman you live with has lived with many or with nobody.”

74-75. He enjoyed the favors of Laïs, as Sotion states in the second book of his Successions of Philosophers. To those who censured him his defense was, “I have Lais, not she me; and it is not abstinence from pleasures that is best, but mastery over them without ever being worsted.”

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925</blockquote>

Aristippus: Tyrant Dionysius

Plutarch, Life of Dion 19.7

<blockquote>Thereupon Aristippus, jesting with the rest of the philosophers, said that he himself also could predict something strange. And when they besought him to tell what it was, “Well, then,” said he, “I predict that ere long Plato and Dionysius will become enemies.”

Source: Plutarch's Lives translated by Bernadotte Perrin

Loeb Classical Library, 1919</blockquote>

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae Book 12 544.c-d

<blockquote>Accordingly, Hegesander says that once, when he was assigned a very mean place at a banquet by Dionysius, he endured it patiently; and when Dionysius asked him what he thought of his present place, in comparison of his yesterday's seat, he said, “That the one was much the same as the other; for that one,” says he, “is a mean seat today, because it is deprived of me; but it was yesterday the most respectable seat in the room, owing to me: and this one today has become respectable, because of my presence in it; but yesterday it was an inglorious seat, as I was not present in it.” And in another place Hegesander says- “Aristippus, being ducked with water by Dionysius' servants, and being ridiculed by Antiphon for bearing it patiently, said, 'But suppose I had been out fishing, and got wet, was I to have left my employment, and come away?'”

Source: Athenaeus, Deipnosophists.

Translated by C. D. Yonge, 1854</blockquote>

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.67,69,70,73,75,77-78,79,80,81,82

<blockquote>67. And when Dionysius gave him his choice of three courtesans, he carried off all three, saying, “Paris paid dearly for giving the preference to one out of three.” And when he had brought them as far as the porch, he let them go. To such lengths did he go both in choosing and in disdaining. Hence the remark of Strato, or by some accounts of Plato, “You alone are endowed with the gift to flaunt in robes or go in rags.” He bore with Dionysius when he spat on him, and to one who took him to task he replied, “If the fishermen let themselves be drenched with sea-water in order to catch a gudgeon, ought I not to endure to be wetted with negus in order to take a blenny?”

69. When Dionysius inquired what was the reason that philosophers go to rich men's houses, while rich men no longer visit philosophers, his reply was that “the one know what they need while the other do not.” When he was reproached by Plato for his extravagance, he inquired, “Do you think Dionysius a good man?” and the reply being in the affirmative, “And yet,” said he, “he lives more extravagantly than I do. So that there is nothing to hinder a man living extravagantly and well.”

70. In answer to one who remarked that he always saw philosophers at rich men's doors, he said, “So, too, physicians are in attendance on those who are sick, but no one for that reason would prefer being sick to being a physician.”

73. Being once compelled by Dionysius to enunciate some doctrine of philosophy, “It would be ludicrous,” he said, “that you should learn from me what to say, and yet instruct me when to say it.” At this, they say, Dionysius was offended and made him recline at the end of the table. And Aristippus said, “You must have wished to confer distinction on the last place.”

75. One day Simus, the steward of Dionysius, a Phrygian by birth and a rascally fellow, was showing him costly houses with tesselated pavements, when Aristippus coughed up phlegm and spat in his face. And on his resenting this he replied, “I could not find any place more suitable.”

77-78. Dionysius once asked him what he was come for, and he said it was to impart what he had and obtain what he had not. But some make his answer to have been, “When I needed wisdom, I went to Socrates; now that I am in need of money, I come to you.”

78. One day Dionysius over the wine commanded everybody to put on purple and dance. Plato declined, quoting the line:

I could not stoop to put on women's robes.

Aristippus, however, put on the dress and, as he was about to dance, was ready with the repartee:

Even amid the Bacchic revelry

True modesty will not be put to shame.

79. He made a request to Dionysius on behalf of a friend and, failing to obtain it, fell down at his feet. And when some one jeered at him, he made reply, “It is not I who am to blame, but Dionysius who has his ears in his feet.”

80. To the critic who censured him for leaving Socrates to go to Dionysius, his rejoinder was, “Yes, but I came to Socrates for education and to Dionysius for recreation.”

81. He received a sum of money from Dionysius at the same time that Plato carried off a book and, when he was twitted with this, his reply was,, “Well, I want money, Plato wants books.” Some one asked him why he let himself be refuted by Dionysius. “For the same reason,” said he, “as the others refute him.”

82. Dionysius met a request of his for money with the words, “Nay, but you told me that the wise man would never be in want.” To which he retorted, “Pay! Pay! and then let us discuss the question;” and when he was paid, “Now you see, do you not,” said he, “that I was not found wanting?” Dionysius having repeated to him the lines:

Whoso betakes him to a prince's court Becomes his slave, albeit of free birth,

he retorted:

If a free man he come, no slave is he.

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925</blockquote>

Aristippus: Xenophon's Testimony

Xenophon, Memorabilia Book 2.1

<blockquote>Now, if the effect of such discourses was, as I imagine, to deter his hearers from the paths of quackery and false-seeming, so I am sure that language like the following was calculated to stimulate his followers to practise self-control and endurance: self-control in the matters of eating, drinking, sleeping, and the cravings of lust; endurance of cold and heat and toil and pain. He had noticed the undue licence which one of his acquaintances allowed himself in all such matters. Accordingly he thus addressed him:

Tell me, Aristippus (Socrates said), supposing you had two children entrusted to you to educate, one of them must be brought up with an aptitude for government, and the other without the faintest propensity to rule—how would you educate them? What do you say? Shall we begin our inquiry from the beginning, as it were, with the bare elements of food and nutriment?

Ar. Yes, food to begin with, by all means, being a first principle, without which there is no man living but would perish.

Soc. Well, then, we may expect, may we not, that a desire to grasp food at certain seasons will exhibit itself in both the children?

Ar. It is to be expected.

Soc. Which, then, of the two must be trained, of his own free will, to prosecute a pressing business rather than gratify the belly?

Ar. No doubt the one who is being trained to govern, if we would not have affairs of state neglected during his government.

Soc. And the same pupil must be furnished with a power of holding out against thirst also when the craving to quench it comes upon him?

Ar. Certainly he must.

Soc. And on which of the two shall we confer such self-control in regard to sleep as shall enable him to rest late and rise early, or keep vigil, if the need arise?

Ar. To the same one of the two must be given that endurance also.

Soc. Well, and a continence in regard to matters sexual so great that nothing of the sort shall prevent him from doing his duty? Which of them claims that?

Ar. The same one of the pair again.

Soc. Well, and on which of the two shall be bestowed, as a further gift, the voluntary resolution to face toils rather than turn and flee from them?

Ar. This, too, belongs of right to him who is being trained for government.

Soc. Well, and to which of them will it better accord to be taught all knowledge necessary towards the mastery of antagonists?

Ar. To our future ruler certainly, for without these parts of learning all his other capacities will be merely waste.

Soc. Will not a man so educated be less liable to be entrapped by rival powers, and so escape a common fate of living creatures, some of which (as we all know) are hooked through their own greediness, and often even in spite of a native shyness; but through appetite for food they are drawn towards the bait, and are caught; while others are similarly ensnared by drink?

Ar. Undoubtedly.

Soc. And others again are victims of amorous heat, as quails, for instance, or partridges, which, at the cry of the hen-bird, with lust and expectation of such joys grow wild, and lose their power of computing dangers: on they rush, and fall into the snare of the hunter?

Aristippus assented.

Soc. And would it not seem to be a base thing for a man to be affected like the silliest bird or beast? as when the adulterer invades the innermost sanctum of the house, though he is well aware of the risks which his crime involves, the formidable penalties of the law, the danger of being caught in the toils, and then suffering the direst contumely. Considering all the hideous penalties which hang over the adulterer's head, considering also the many means at hand to release him from the thraldom of his passion, that a man should so drive headlong on to the quicksands of perdition —what are we to say of such frenzy? The wretch who can so behave must surely be tormented by an evil spirit?

Ar. So it strikes me.

Soc. And does it not strike you as a sign of strange indifference that, whereas the greater number of the indispensable affairs of men, as for instance, those of war and agriculture, and more than half the rest, need to be conducted under the broad canopy of heaven, yet the majority of men are quite untrained to wrestle with cold and heat?

Aristippus again assented.

Soc. And do you not agree that he who is destined to rule must train himself to bear these things lightly?

Ar. Most certainly.

Soc. And whilst we rank those who are self-disciplined in all these matters among persons fit to rule, we are bound to place those incapable of such conduct in the category of persons without any pretension whatsoever to be rulers?

Ar. I assent.

Soc. Well, then, since you know the rank peculiar to either section of mankind, did it ever strike you to consider to which of the two you are best entitled to belong?

Yes I have (replied Aristippus). I do not dream for a moment of ranking myself in the class of those who wish to rule. In fact, considering how serious a business it is to cater for one's own private needs, I look upon it as the mark of a fool not to be content with that, but to further saddle oneself with the duty of providing the rest of the community with whatever they may be pleased to want. That, at the cost of much personal enjoyment, a man should put himself at the head of a state, and then, if he fail to carry through every jot and tittle of that state's desire, be held to criminal account, does seem to me the very extravagance of folly. Why, bless me! states claim to treat their rulers precisely as I treat my domestic slaves. I expect my attendants to furnish me with an abundance of necessaries, but not to lay a finger on one of them themselves. So these states regard it as the duty of a ruler to provide them with all the good things imaginable, but to keep his own hands off them all the while. So then, for my part, if anybody desires to have a heap of pother himself, and be a nuisance to the rest of the world, I will educate him in the manner suggested, and he shall take his place among those who are fit to rule; but for myself, I beg to be enrolled amongst those who wish to spend their days as easily and pleasantly as possible.

Soc. Shall we then at this point turn and inquire which of the two are likely to lead the pleasanter life, the rulers or the ruled?

Ar. By all means let us do so.

Soc. To begin then with the nations and races known to ourselves. In Asia the Persians are the rulers, while the Syrians, Phrygians, Lydians are ruled; and in Europe we find the Scythians ruling, and the Maeotians being ruled. In Africa the Carthaginians are rulers, the Libyans ruled. Which of these two sets respectively leads the happier life, in your opinion? Or, to come nearer home—you are yourself a Hellene—which among Hellenes enjoy the happier existence, think you, the dominant or the subject states?

Nay, I would have you to understand (exclaimed Aristippus) that I am just as far from placing myself in the ranks of slavery; there is, I take it, a middle path between the two which it is my ambition to tread, avoiding rule and slavery alike; it lies through freedom—the high road which leads to happiness.

Soc. True, if only your path could avoid human beings, as it avoids rule and slavery, there would be something in what you say. But being placed as you are amidst human beings, if you purpose neither to rule nor to be ruled, and do not mean to dance attendance, if you can help it, on those who rule, you must surely see that the stronger have an art to seat the weaker on the stool of repentance both in public and in private, and to treat them as slaves. I daresay you have not failed to note this common case: a set of people has sown and planted, whereupon in comes another set and cuts their corn and fells their fruit-trees, and in every way lays siege to them because, though weaker, they refuse to pay them proper court, till at length they are persuaded to accept slavery rather than war against their betters. And in private life also, you will bear me out, the brave and powerful are known to reduce the helpless and cowardly to bondage, and to make no small profit out of their victims.

Ar. Yes, but I must tell you I have a simple remedy against all such misadventures. I do not confine myself to any single civil community. I roam the wide world a foreigner.

Soc. Well, now, that is a masterly stroke, upon my word! Of course, ever since the decease of Sinis, and Sciron, and Procrustes, foreign travellers have had an easy time of it. But still, if I bethink me, even in these modern days the members of free communities do pass laws in their respective countries for self-protection against wrong-doing. Over and above their personal connections, they provide themselves with a host of friends; they gird their cities about with walls and battlements; they collect armaments to ward off evil-doers; and to make security doubly sure, they furnish themselves with allies from foreign states. In spite of all which defensive machinery these same free citizens do occasionally fall victims to injustice. But you, who are without any of these aids; you, who pass half your days on the high roads where iniquity is rife; you, who, into whatever city you enter, are less than the least of its free members, and moreover are just the sort of person whom any one bent on mischief would single out for attack—yet you, with your foreigner's passport, are to be exempt from injury? So you flatter yourself. And why? Will the state authorities cause proclamation to be made on your behalf: “The person of this man Aristippus is secure; let his going out and his coming in be free from danger”? Is that the ground of your confidence? or do you rather rest secure in the consciousness that you would prove such a slave as no master would care to keep? For who would care to have in his house a fellow with so slight a disposition to work and so strong a propensity to extravagance? Suppose we stop and consider that very point: how do masters deal with that sort of domestic? If I am not mistaken, they chastise his wantonness by starvation; they balk his thieving tendencies by bars and bolts where there is anything to steal; they hinder him from running away by bonds and imprisonment; they drive the sluggishness out of him with the lash. Is it not so? Or how do you proceed when you discover the like tendency in one of your domestics?

Ar. I correct them with all the plagues, till I force them to serve me properly. But, Socrates, to return to your pupil educated in the royal art, which, if I mistake not, you hold to be happiness: how, may I ask, will he be better off than others who lie in evil case, in spite of themselves, simply because they suffer perforce, but in his case the hunger and the thirst, the cold shivers and the lying awake at nights, with all the changes he will ring on pain, are of his own choosing? For my part I cannot see what difference it makes, provided it is one and the same bare back which receives the stripes, whether the whipping be self-appointed or unasked for; nor indeed does it concern my body in general, provided it be my body, whether I am beleaguered by a whole armament of such evils of my own will or against my will—except only for the folly which attaches to self-appointed suffering.

Soc. What, Aristippus, does it not seem to you that, as regards such matters, there is all the difference between voluntary and involuntary suffering, in that he who starves of his own accord can eat when he chooses, and he who thirsts of his own free will can drink, and so for the rest; but he who suffers in these ways perforce cannot desist from the suffering when the humour takes him? Again, he who suffers hardship voluntarily, gaily confronts his troubles, being buoyed on hope —just as a hunter in pursuit of wild beasts, through hope of capturing his quarry, finds toil a pleasure—and these are but prizes of little worth in return for their labours; but what shall we say of their reward who toil to obtain to themselves good friends, or to subdue their enemies, or that through strength of body and soul they may administer their households well, befriend their friends, and benefit the land which gave them birth? Must we not suppose that these too will take their sorrows lightly, looking to these high ends? Must we not suppose that they too will gaily confront existence, who have to support them not only their conscious virtue, but the praise and admiration of the world? And once more, habits of indolence, along with the fleeting pleasures of the moment, are incapable, as gymnastic trainers say, of setting up a good habit of body, or of implanting in the soul any knowledge worthy of account; whereas by painstaking endeavour in the pursuit of high and noble deeds, as good men tell us, through endurance we shall in the end attain the goal. So Hesiod somewhere says:

Wickedness may a man take wholesale with ease, smooth is the way and her dwelling-place is very nigh; but in front of virtue the immortal gods have placed toil and sweat, long is the path and steep that leads to her, and rugged at the first, but when the summit of the pass is reached, then for all its roughness the path grows easy.

And Ephicharmus bears his testimony when he says:

The gods sell us all good things in return for our labours.

And again in another passage he exclaims:

Set not thine heart on soft things, thou knave, lest thou light upon the hard.

And that wise man Prodicus delivers himself in a like strain concerning virtue in that composition of his about Heracles, which crowds have listened to. This, as far as I can recollect it, is the substance at least of what he says:

“When Heracles was emerging from boyhood into the bloom of youth, having reached that season in which the young man, now standing upon the verge of independence, shows plainly whether he will enter upon the path of virtue or of vice, he went forth into a quiet place, and sat debating with himself which of those two paths he should pursue; and as he there sat musing, there appeared to him two women of great stature which drew nigh to him. The one was fair to look upon, frank and free by gift of nature, her limbs adorned with purity and her eyes with bashfulness; sobriety set the rhythm of her gait, and she was clad in white apparel. The other was of a different type; the fleshy softness of her limbs betrayed her nurture, while the complexion of her skin was embellished that she might appear whiter and rosier than she really was, and her figure that she might seem taller than nature made her; she stared with wide-open eyes, and the raiment wherewith she was clad served but to reveal the ripeness of her bloom. With frequent glances she surveyed her person, or looked to see if others noticed her; while ever and anon she fixed her gaze upon the shadow of herself intently.

“Now when these two had drawn near to Heracles, she who was first named advanced at an even pace towards him, but the other, in her eagerness to outstrip her, ran forward to the youth, exclaiming, 'I see you, Heracles, in doubt and difficulty what path of life to choose; make me your friend, and I will lead you to the pleasantest road and easiest. This I promise you: you shall taste all of life's sweets and escape all bitters. In the first place, you shall not trouble your brain with war or business; other topics shall engage your mind; your only speculation, what meat or drink you shall find agreeable to your palate; what delight of ear or eye; what pleasure of smell or touch; what darling lover's intercourse shall most enrapture you; how you shall pillow your limbs in softest slumber; how cull each individual pleasure without alloy of pain; and if ever the suspicion steal upon you that the stream of joys will one day dwindle, trust me I will not lead you where you shall replenish the store by toil of body and trouble of soul. No! others shall labour, but you shall reap the fruit of their labours; you shall withhold your hand from nought which shall bring you gain. For to all my followers I give authority and power to help themselves freely from every side.'

“Heracles hearing these words made answer: 'What, O lady, is the name you bear?' To which she: 'Know that my friends call be Happiness, but they that hate me have their own nicknames for me, Vice and Naughtiness.'

“But just then the other of those fair women approached and spoke: 'Heracles, I too am come to you, seeing that your parents are well known to me, and in your nurture I have gauged your nature; wherefore I entertain good hope that if you choose the path which leads to me, you shall greatly bestir yourself to be the doer of many a doughty deed of noble emprise; and that I too shall be held in even higher honour for your sake, lit with the lustre shed by valorous deeds. I will not cheat you with preludings of pleasure, but I will relate to you the things that are according to the ordinances of God in very truth. Know then that among things that are lovely and of good report, not one have the gods bestowed upon mortal men apart from toil and pains. Would you obtain the favour of the gods, then must you pay these same gods service; would you be loved by your friends, you must benefit these friends; do you desire to be honoured by the state, you must give the state your aid; do you claim admiration for your virtue from all Hellas, you must strive to do some good to Hellas; do you wish earth to yield her fruits to you abundantly, to earth must you pay your court; do you seek to amass riches from your flocks and herds, on them must you bestow your labour; or is it your ambition to be potent as a warrior, able to save your friends and to subdue your foes, then must you learn the arts of war from those who have the knowledge, and practise their application in the field when learned; or would you e'en be powerful of limb and body, then must you habituate limbs and body to obey the mind, and exercise yourself with toil and sweat.'

“At this point, (as Prodicus relates) Vice broke in exclaiming: 'See you, Heracles, how hard and long the road is by which yonder woman would escort you to her festal joys. But I will guide you by a short and easy road to happiness.'

“Then spoke Virtue: 'Nay, wretched one, what good thing hast thou? or what sweet thing art thou acquainted with—that wilt stir neither hand nor foot to gain it? Thou, that mayest not even await the desire of pleasure, but, or ever that desire springs up, art already satiated; eating before thou hungerest, and drinking before thou thirsteth; who to eke out an appetite must invent an army of cooks and confectioners; and to whet thy thirst must lay down costliest wines, and run up and down in search of ice in summer-time; to help thy slumbers soft coverlets suffice not, but couches and feather-beds must be prepared thee and rockers to rock thee to rest; since desire for sleep in thy case springs not from toil but from vacuity and nothing in the world to do. Even the natural appetite of love thou forcest prematurely by every means thou mayest devise, confounding the sexes in thy service. Thus thou educatest thy friends: with insult in the night season and drowse of slumber during the precious hours of the day. Immortal, thou art cast forth from the company of gods, and by good men art dishonoured: that sweetest sound of all, the voice of praise, has never thrilled thine ears; and the fairest of all fair visions is hidden from thine eyes that have never beheld one bounteous deed wrought by thine own hand. If thou openest thy lips in speech, who will believe thy word? If thou hast need of aught, none shall satisfy thee. What sane man will venture to join thy rablle rout? Ill indeed are thy revellers to look upon, young men impotent of body, and old men witless in mind: in the heyday of life they batten in sleek idleness, and wearily do they drag through an age of wrinkled wretchedness: and why? they blush with shame at the thought of deeds done in the past, and groan for weariness at what is left to do. During their youth they ran riot through their sweet things, and laid up for themselves large store of bitterness against the time of eld. But my companionship is with the gods; and with the good among men my conversation; no bounteous deed, divine or human, is wrought without my aid. Therefore am I honoured in Heaven pre-eminently, and upon earth among men whose right it is to honour me; as a beloved fellow-worker of all craftsmen; a faithful guardian of house and lands, whom the owners bless; a kindly helpmeet of servants; a brave assistant in the labours of peace; an unflinching ally in the deeds of war; a sharer in all friendships indispensable. To my friends is given an enjoyment of meats and drinks, which is sweet in itself and devoid of trouble, in that they can endure until desire ripens, and sleep more delicious visits them than those who toil not. Yet they are not pained to part with it; nor for the sake of slumber do they let slip the performance of their duties. Among my followers the youth delights in the praises of his elders, and the old man glories in the honour of the young; with joy they call to memory their deeds of old, and in to-day's well-doing are well pleased. For my sake they are dear in the sight of God, beloved of their friends and honoured by the country of their birth. When the appointed goal is reached they lie not down in oblivion with dishonour, but bloom afresh—their praise resounded on the lips of men for ever. Toils like these, O son of noble parents, Heracles, it is yours to meet with, and having endured, to enter into the heritage assured you of transcendant happiness.'”

This, Aristippus, in rough sketch is the theme which Prodicus pursues in his “Education of Heracles by Virtue,” only he decked out his sentiments, I admit, in far more magnificent phrases than I have ventured on. Were it not well, Aristippus, to lay to heart these sayings, and to strive to bethink you somewhat of that which touches the future of our life?

Source: The Memorabilia Recollections of Socrates

By Xenophon, Translator: H. G. Dakyns

Gutenberg Release Date: August 24, 2008 [EBook #1177]</blockquote>

Xenophon, Memorabilia Book 3.8

<blockquote> Once when Aristippus set himself to subject Socrates to a cross-examination, such as he had himself undergone at the hands of Socrates on a former occasion, Socrates, being minded to benefit those who were with him, gave his answers less in the style of a debater guarding against perversions of his argument, than of a man persuaded of the supreme importance of right conduct.

Aristippus asked him “if he knew of anything good,” intending in case he assented and named any particular good thing, like food or drink, or wealth, or health, or strength, or courage, to point out that the thing named was sometimes bad. But he, knowing that if a thing troubles us, we immediately want that which will put an end to our trouble, answered precisely as it was best to do.

Soc. Do I understand you to ask me whether I know anything good for fever?

No (he replied), that is not my question.

Soc. Then for inflammation of the eyes?

Aristip. No, nor yet that.

Soc. Well then, for hunger?

Aristip. No, nor yet for hunger.

Well, but (answered Socrates) if you ask me whether I know of any good thing which is good for nothing, I neither know of it nor want to know.

And when Aristippus, returning to the charge, asked him “if he knew of any thing beautiful.”

He answered: Yes, many things.

Aristip. Are they all like each other?

Soc. On the contrary, they are often as unlike as possible.

How then (he asked) can that be beautiful which is unlike the beautiful?

Soc. Bless me! for the simple reason that it is possible for a man who is a beautiful runner to be quite unlike another man who is a beautiful boxer, or for a shield, which is a beautiful weapon for the purpose of defence, to be absolutely unlike a javelin, which is a beautiful weapon of swift and sure discharge.

Aristip. Your answers are no better now than when I asked you whether you knew any good thing. They are both of a pattern.

Soc. And so they should be. Do you imagine that one thing is good and another beautiful? Do not you know that relatively to the same standard all things are at once beautiful and good? In the first place, virtue is not a good thing relatively to one standard and a beautiful thing relatively to another standard; and in the next place, human beings, on the same principle and relatively to the same standard, are called “beautiful and good”; and so the bodily frames of men relatively to the same standards are seen to be “beautiful and good,” and in general all things capable of being used by man are regarded as at once beautiful and good relatively to the same standard—the standing being in each case what the thing happens to be useful for.

Aristip. Then I presume even a basket for carrying dung is a beautiful thing?

Soc. To be sure, and a spear of gold an ugly thing, if for their respective uses—the former is well and the latter ill adapted.

Aristip. Do you mean to assert that the same things may be beautiful and ugly?

Soc. Yes, to be sure; and by the same showing things may be good and bad: as, for instance, what is good for hunger may be bad for fever, and what is good for fever bad for hunger; or again, what is beautiful for wrestling is often ugly for running; and in general everything is good and beautiful when well adapted for the end in view, bad and ugly when ill adapted for the same.

Similarly when he spoke about houses, and argued that “the same house must be at once beautiful and useful”—I could not help feeling that he was giving a good lesson on the problem: “how a house ought to be built.” He investigated the matter thus:

Soc. “Do you admit that any one purposing to build a perfect house will plan to make it at once as pleasant and as useful to live in as possible?” and that point being admitted, the next question would be:

“It is pleasant to have one's house cool in summer and warm in winter, is it not?” and this proposition also having obtained assent, “Now, supposing a house to have a southern aspect, sunshine during winter will steal in under the verandah, but in summer, when the sun traverses a path right over our heads, the roof will afford an agreeable shade, will it not? If, then, such an arrangement is desirable, the southern side of a house should be built higher to catch the rays of the winter sun, and the northern side lower to prevent the cold winds finding ingress; in a word, it is reasonable to suppose that the pleasantest and most beautiful dwelling place will be one in which the owner can at all seasons of the year find the pleasantest retreat, and stow away his goods with the greatest security.”

Paintings and ornamental mouldings are apt (he said) to deprive one of more joy than they confer.

The fittest place for a temple or an altar (he maintained) was some site visible from afar, and untrodden by foot of man: (18) since it was a glad thing for the worshipper to lift up his eyes afar off and offer up his orison; glad also to wend his way peaceful to prayer unsullied.

Source: The Memorabilia Recollections of Socrates

By Xenophon, Translator: H. G. Dakyns

Gutenberg Release Date: August 24, 2008 [EBook #1177]</blockquote>

Aristippus: Other Testimony

Diogenes Laertius, Life of Aristippus 2.68,70,71,72,73,82-3

<blockquote>68. Diogenes, washing the dirt from his vegetables, saw him passing and jeered at him in these terms, “If you had learnt to make these your diet, you would not have paid court to kings,” to which his rejoinder was, “And if you knew how to associate with men, you would not be washing vegetables.” Being asked what he had gained from philosophy, he replied, “The ability to feel at ease in any society.” Being reproached for his extravagance, he said, “If it were wrong to be extravagant, it would not be in vogue at the festivals of the gods.”

70. Some one brought him a knotty problem with the request that he would untie the knot. “Why, you simpleton,” said he, “do you want it untied, seeing that it causes trouble enough as it is?” “It is better,” he said, “to be a beggar than to be uneducated; the one needs money, the others need to be humanized.” One day that he was reviled, he tried to slip away; the other pursued him, asking, “Why do you run away?” “Because,” said he, “as it is your privilege to use foul language, so it is my privilege not to listen.” In answer to one who remarked that he always saw philosophers at rich men's doors, he said, “So, too, physicians are in attendance on those who are sick, but no one for that reason would prefer being sick to being a physician.”

71. It happened once that he set sail for Corinth and, being overtaken by a storm, he was in great consternation. Some one said, “We plain men are not alarmed, and are you philosophers turned cowards?” To this he replied, “The lives at stake in the two cases are not comparable.”

72. He gave his daughter Arete the very best advice, training her up to despise excess. He was asked by some one in what way his son would be the better for being educated. He replied, “If nothing more than this, at all events, when in the theatre he will not sit down like a stone upon stone.”

73. Being asked on one occasion what is the difference between the wise man and the unwise, “Strip them both,” said he, “and send them among strangers and you will know.”

82-83. This is stated by Diocles in his work On the Lives of Philosophers; other writers refer the anecdotes to Plato. After getting in a rage with Aeschines, he presently addressed him thus: “Are we not to make it up and desist from vapouring, or will you wait for some one to reconcile us over the wine-bowl?” To which he replied, “Agreed.” “Then remember,” Aristippus went on, “that, though I am your senior, I made the first approaches.” Thereupon Aeschines said, “Well done, by Hera, you are quite right; you are a much better man than I am. For the quarrel was of my beginning, you make the first move to friendship.” Such are the repartees which are attributed to him.

Source: Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Issues 184-185 of Loeb Classical Library

Translated by Robert Drew Hicks

Harvard University Press, 1925</blockquote>

Plutarch, Concerning Anger

<blockquote>And Aristippus, when there happened to be a falling out between him and Aeschines, and one said to him, O Aristippus, what is now become of the friendship that was between you two? answered, It is asleep, but I will go and awaken it. Then coming to Aeschines, he said to him, What? do you take me to be so utterly wretched and incurable as not to be worth your admonition? No wonder, said Aeschines, if you, by nature so excelling me in every thing, did here also discern before me what was right and fitting to be done.

English Modernized

Source: Plutarch's Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands.

Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878).\\</blockquote>

Plutarch, Sensibility in the Progress of Virtue

<blockquote>Aristippus was a great example of this; for when in a set disputation he was baffled by the sophistry and forehead of an impudent, wild, and ignorant disputant, and observed him to be flushed and high with the conquest; Well! says the philosopher, I am certain, I shall sleep quieter to-night than my antagonist.

Source: Plutarch's Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands.

Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878).</blockquote>

Aelian, Various Histories Book 9.20

<blockquote>Of Aristippus. Aristippus being in a great storm at Sea, one of those who were aboard with him said, “Are you afraid too, Aristippus, as well as we of the ordinary sort?” “Yes, answered he, and with reason; for you shall only lose a wicked life, but I, Felicity.”

Source: Aelian. His Various History (Varia Historia).

Thomas Stanley, translator (1665)</blockquote>

Relations of Aristippus: Doctrines and Persons

Arete: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology