Table of Contents

Sardis

Definition

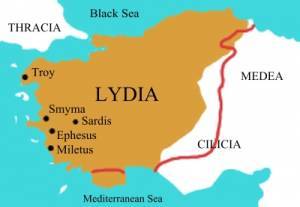

Sardis was an important ancient city and capital of the kingdom of Lydia, located in western Anatolia, present-day Sartmustafa, Manisa province in western Turkey. Its strategic location made it a central point connecting the interior of Anatolia to the Aegean coast. During its history, control of Sardis changed many times, but it always kept a high status among cities.

The Origin of Sardis

Around 612 BCE, the greatest city in the world at that time, Nineveh, was besieged and sacked by an allied army of Persians, Medes, rebelling Chaldeans, and Babylonians, putting an end to the Assyrian Empire. This event shaped a new political map: Babylon became the imperial centre of Mesopotamia and the kingdom of Lydia became the dominant power in western Anatolia with Sardis as its capital.

The life of Sardis began as a hilltop citadel where the king of Lydia lived. The city developed into a two part town: the lower town, located along the banks of the Pactolus river, where the ordinary citizens lived, and the upper town for the wealthy citizens, royal members, and the palace. Herodotus wrote that the lower town was a modest place with many of its houses made of reeds from the river and with no surrounding wall.

Relations with the Greek World

To the west, Lydia had the Greek colonies of Ionia. After the fall of Assyria, Lydia was free to turn its attention to the Ionian cities, which became dominated by Lydia. Lydian rulers, however, admired the Greeks and treated the Ionian cities leniently. Moreover, Croesus, the last Lydian king, even paid for the construction of the temple of Artemis, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Thus, the Ionian coast city-states and the Lydians remained on peaceful terms with very tight cultural and commercial relations. Sardis was a centre for the traffic of goods and ideas between Mesopotamia and the Greek Ionian settlements, a crossroad of trade, and an ideal meeting point for the exchange of ideas, beliefs, customs, knowledge, and new insights. This rich exchange was one of the factors that, around 600 BCE, allowed the Ionian cities to turn into the intellectual leaders of the Greek world.

Herodotus (1.31) claims that on one occasion Sardis was visited by Solon, a famous Athenian lawmaker and statesman and one of the seven proverbial wise men of ancient Hellas, who met Croesus, the Lydian king. This meeting between Solon and Croesus is certainly a fiction: Solon, if we trust the current accepted chronology, must have been dead several years before 560 BCE, the year when Croesus became king of Lydia. Nevertheless, according to the story Croesus was overjoyed to have such an important visitor and was anxious to display his wealth to the well-travelled Solon. Croesus finally asked Solon who, of all the men he had met in his travels, he would call the most happy. Solon replied, “Tellus of Athens.” This made Croesus upset since he expected to be named first. Solon added that Tellus had lived well and happily, had a beautiful family, and had died gloriously for Athens in battle. Croesus agreed this was a good life and asked Solon who else he would consider to be among the happiest of men he had met, hoping he would at least be named second. Solon answered “Cleobis and Biton”, two Greek brothers who had enough resources to live, great fitness levels, and who had died honourably. Croesus, angered now, shouted, “My Athenian guest, are you disparaging my own happiness as though it were nothing?, Do you think me less than a common man?” Solon replied that no person can be judged fortunate until their death: “I cannot yet tell you the answer you asked for until I learn how you have ended your life.”

Persian Control

When Cyrus II, King of Persia, invaded Sardis in 547 BCE, it became obvious that the lack of a defensive wall protecting the lower city was not a wise choice. The Lydian king Croesus simply retreated to the upper town, and the Persian army controlled the lower city with very little resistance. The Persian army finally found an unguarded spot in the citadel’s defences, and Sardis came under Persian control for the next two centuries.

During the Persian occupation, Sardis did not change much: A Persian garrison was built on the acropolis while the lower town settlements remained unchanged. An altar of Artemis is mentioned by Xenophon, possibly in the southern portion of the acropolis, in the settlements along the river, where some time later a temple to the goddess was built.

Once Sardis was taken, the Persians also occupied the Ionian cities. About 500 BCE, the Ionian cities dismissed the Persian authorities and declared their independence, triggering the Ionian revolt with the city of Miletus as the leading state, the first of many military conflicts between Greeks and Persians. A Greek army marched upon Sardis and burned it to the ground. This is how Herodotus reports the incident:

<blockquote>When the Athenians, the Eretrians, and the rest of the allies had arrived and were present in Miletus, Aristagoras organized an expedition against Sardis. […] they journeyed inland in massive force, with Ephesians as their guides. They travelled along the Cayster River, crossed over Mount Tmolus, and came to Sardis, where they captured the city without resistance from anyone whatsoever. They took control of everything except the acropolis. For Artaphernes [the brother of the Persian king, Darius I] himself defended the acropolis with a rather large force of men.

Although they had taken the city, they were unable to plunder it because most of the houses in Sardis were constructed of reeds […] and when a soldier set one of these houses on fire, the flames spread rapidly from house to house until they engulfed the entire city.

(Herodotus, 5.99-101)</blockquote>

Macedonian & Seleucid Control

A number of changes took place in Sardis after the city surrendered to Alexander the Great in 334 BCE. A new lower town was built to the north of the Acropolis and the old town was gradually abandoned, with the sole exception of the Temple of Artemis and its surrounding area, where a few citizens continued to live. The new lower town had the east-west road as its axis which connected the interior to the coast.

A number of Hellenistic public buildings were built in the new town including a stadium and a theatre. The city was walled at some point before the year 215 BCE as attested to by ancient reports that, when the troops led by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III assaulted Sardis that year, they penetrated across a section of the city wall near the theatre. Sardis was then made Seleucid’s administrative centre for the Anatolia region.

Roman Control

Sardis came under Roman rule in 133 BCE. During this time, it remained an important city and was the principal centre of a judicial district that included almost 30 Lydian and Phrygian settlements. The city was eventually made a provincial capital when Lydia was re-established as an administrative centre.

Tacitus reports an earthquake that affected the city in 17 CE:

<blockquote>That same year twelve famous cities of Asia fell by an earthquake in the night, so that the destruction was all the more unforeseen and fearful. Nor were there the means of escape usual in, such a disaster, by rushing out into the open country, for there people were swallowed up by the yawning earth. Vast mountains, it is said, collapsed; what had been level ground seemed to be raised aloft, and fires blazed out amid the ruin. The calamity fell most fatally on the inhabitants of Sardis, and it attracted to them the largest share of sympathy.

(Tacitus, 2.47)</blockquote>

During the second and early 3rd century CE, the city expanded to the west. At the beginning of the 5th century a wall enclosing 156 hectares was built. Then in the year 616 CE, Sardis' life came to an end. A Persian army penetrated the Roman defensive lines that had been deployed in eastern Anatolia. Soon after, part of that region fell to the Persians, including Sardis. The city fortifications could not do much to stop the Persian troops, and Sardis was sacked and devastated so completely that no attempt to restore the city has been recorded. This incident constitutes the end of Sardis’ civic life. A military detachment regained the citadel in 660 CE, but the town itself remained empty and all subsequent references to Sardis are to the castle on the hill, never to the town.

Sardis Today

Since 1958 CE, the universities of Harvard and Cornell have been performing annual excavations at Sardis. As part of these works, Sardis’ gymnasium has been restored and the synagogue was discovered in 1962 CE, a building measuring over 91.4 metres (300 feet) in length. Some of the important finds from the archaeological site of Sardis are kept in the Archaeological Museum of Manisa in Turkey, including many Roman mosaics and sculptures and pottery from different periods in the history of the city.

Written by Cristian Violatti, published on 20 March 2014 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms.