Table of Contents

Battle of Hydaspes

Article

For almost a decade, Alexander the Great and his army swept across Western Asia and into Egypt, defeating King Darius III and the Persians at the battles of River Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela. Next, despite the objections of the loyal army who had been with him since leaving Macedonia in 334 BCE, he turned his attention southward towards India. It was there, in 326 BCE, that he would achieve what many would consider as his last major victory, the Battle of Hydaspes (in modern Pakistan). In the view of one historian it would be Alexander at his very best - a fitting climax to his conquests of Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt and Persia. At Hydaspes he would meet a formidable opponent in King Porus, but more importantly, his military savvy would be challenged as never before by an unforgiving climate and a new, even larger foe, the elephant.

Battle of Hydaspes

The Battle of Hydaspes has been viewed by many as an ambitious undertaking, beyond anything Alexander had ever done, but the young king understood that in order to continue his march across India he had to defeat King Porus. Alexander’s initial march across India went relatively unchallenged, gaining a number of allies along the way. With the hope of avoiding a battle with the Indian king, he sent an agent to Porus seeking a peaceful resolution, but the proud king refused to pay tribute, telling Alexander that he would meet him in battle. He felt confident, believing his greatest defense lay in the river itself - over a mile wide, deep, and fast moving (unlike the river Granicus). By the time of Alexander’s arrival it would be further swollen by the monsoon season and the melting snow of the Himalayas.

Timing of the Battle

Porus believed and hoped Alexander would have to either wait for the monsoon season to end before crossing or simply abandon his quest and leave. In preparation for the Macedonians’ arrival, he stationed his army in a defensive position along the river and waited. While exact numbers vary, estimates place Porus with 20-50,000 infantry, over 2,000 cavalry, upwards to 200 elephants and more than 300 chariots. As in previous battles, Alexander would be facing an army that outnumbered him, something that never seemed to worry him. Unfortunately for Porus, he had underestimated the brilliance of the young Macedonian king.

As Porus had anticipated, Alexander made camp directly across from him on the west side of the Hydaspes and gave every indication he would wait for the monsoon season to end, even going so far as having large grain shipments sent in from his Indian ally King Taxila (also known as Omphis). But, in reality, he had no intention of waiting. In order to prepare for the inevitable battle, he had gathered support from many of the local rajahs including Taxila - a move Alexander had hoped would anger Porus. Alexander had also arrived at the Hydaspes well-prepared. Before marching into India, he had recruited additional troops from many of the Persian territories he had conquered, training them in the Macedonian style of fighting - a move that had angered the veteran Macedonian soldiers. Lastly, anticipating Porus’ use of elephants, he added Scythian horse-archers.

Preparations

Across the river, Porus was also preparing and waiting with his army of elephants, cavalry, infantry, and six-man chariots. The six-man team of these included two charioteers or mahouts, two shield-bearers, and two archers. Porus believed he had the ultimate advantage; he had only to remain in his defensive position, guard the best potential crossing spots, and slaughter Alexander’s army as they emerged from the river. But, if the Macedonians were successful and crossed, they had to face his elephants. For the first time elephants (although there are some who claim elephants were at Gaugamela) were introduced to the West. While the use of elephants has a positive side (horses hate them), they panic easily and are difficult to control. Still, Alexander and others - including the great Carthaginian Hannibal - would use them in future battles. In his The Life of Alexander the Great historian Plutarch gives an account of Alexander’s arrival at the Hydaspes:

<blockquote>Alexander, in his own letters, has given as account of his war with Porus. He says the two armies were separated by the river Hydaspes, on whose opposite bank Porus continually kept his elephants in order of battle, with their heads towards their enemies, to guard the passage, that he, on the other hand, made every day a great noise and clamour in his camp, to dissipate the apprehensions of the barbarians…</blockquote>

Alexander the Great

Alexander and his army sat across the Hydaspes, facing Porus, each king quite visible to the other. Realizing there might be spies in his camp, Alexander voiced aloud how he could easily wait until the end of the monsoon season before engaging the Indian king in battle. To support his boast he built numerous campfires along his side of the river, marching his men back and forth in formation - all the while searching for a suitable crossing spot. Curiosity drove Porus to initially shadow these movements, finally deciding they were only a diversion and stopped, although he continued to monitor possible crossing locations. In his The Campaigns of Alexander, historian Arrian wrote of this search for a crossing:

<blockquote>Alexander’s answer was by continual movement of his own troops to keep Porus guessing: he split his force into a number of detachments, moving some of them under his own command hither and thither all over the place, destroying enemy possessions and looking for places where the river might be crossed…</blockquote>

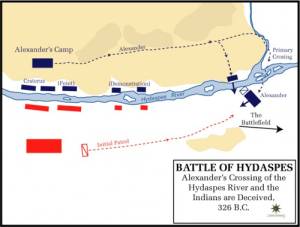

Porus continued to be hopeful that Alexander would simply give up and leave. Some historians believe Porus was unsure whether or not he could defeat the Macedonians. He would soon have his chance to find out. After a long tedious search, a suitable location to cross was found about eighteen miles from the Macedonian camp at a bend in the river - a heavily wooded area that would be the perfect place to provide cover. It was late evening and a terrible thunderstorm was raging, but Alexander and his army were ready.

Crossing the River

In order to keep Porus unaware of his crossing, Alexander left Craterus in camp with a sufficient force and orders not to cross himself until later. One story tells of Alexander leaving a soldier dressed as the king to further confuse Porus. Alexander took with him part of the Companion cavalry, the mounted archers, and several infantry units under Hephaestion, Perdiccos and Demitrios. The crossing was to be in three waves. In order to safely cross the river Alexander made rafts from tents and used the thirty galleys and boats from his crossing of the Indus River. In total he crossed with an estimated 15,000 cavalry and 11,000 infantry. Unfortunately, the crossing did not go as smoothly as he had hoped. Alexander was surprised that instead of reaching the opposite shore he landed on a large island in the middle of the river. From the island to the other side, his men would have to wade across. Of course, there is some disagreement on whether or not Alexander knew of the island - it could have been a mistake or it may have been on purpose. Many do not believe the existence of a large island would have been something Alexander could have missed.

After reaching the shore at dawn, Alexander regrouped his army into battle formation and prepared for his meeting with Porus. The Companion cavalry was stationed in front of the infantry (not all of the infantry had crossed as they would join Alexander later) while the mounted archers served as a defensive screen against the elephants ahead of the cavalry because Alexander was reluctant to have his cavalry advance without protection. Scouts for Porus had already seen the Macedonian’s crossing and informed the Indian king of Alexander’s arrival. Porus prepared to retaliate.

Battle

In a futile attempt to delay Alexander, Porus sent his son with 3,000 cavalry and 120 chariots. This attempt spelled disaster for Porus. Alexander killed the son and destroyed the cavalry and chariots; the few survivors fled back to Porus. Arrian, who most believe has the most accurate account of the battle, addressed this confrontation:

<blockquote>…and the Indians, seeing Alexander there in person and his massed cavalry coming at them in successive charges, squadron by squadron, broke and fled …. Porus’ son being among the killed; their chariots and horses were captured as they attempted to get away…</blockquote>

Without waiting for the additional infantry to cross, Alexander advanced the six miles towards the Indian camp where he would wait for the remainder of his infantry to arrive. “Alexander had no intention of making the fresh enemy troops a present of his own breathless and exhausted men, so he paused before advancing to the attack.” (Arrian). Since most contemporary sources are lost, there is considerable disagreement from later historians over the facts of the battle. However, there is agreement on how Porus prepared to meet the Macedonian army, placing his best weapon, the elephants, on his front line ahead of his infantry. The Indian cavalry was situated on the right and left flanks screened by the six-man chariots. In the middle was Porus astride his elephant.

Alexander the Great in Combat

As with his other battles in Greece and Persia, Alexander relied on many of the same techniques that had proven successful. Most sources agree that Alexander, stationed on the right, used the Companion cavalry to attack Porus’ flanks while his horse archers pelted the elephants with arrows. Coenus, whose initial location is uncertain, attacked Porus’ right flank while Alexander assaulted his left. In a defensive maneuver Porus sent his cavalry from the right to circle back and help his left against Alexander. Next, Porus, who awaited help from his ally King Abisares of Kashmir, sent his elephants against the Macedonian phalanx. Slowly, the infantry pulled back but without breaking ranks as the horse-archers attacked with a barrage of arrows. Unfortunately for the Indian army, the elephants panicked and revolted, actually causing more harm to Porus’ own men than to Alexander. Arrian wrote:

<blockquote>In time the elephants tired and their charges grew feebler, and with nothing worse than trumpeting. Taking his chance, Alexander surrounded the lot of them – elephants, horsemen, and all – and then signaled his infantry to lock shields and move up in a solid mass. Most of the Indian cavalry was cut down in the ensuing action; their infantry, too, hard pressed by the Macedonians, suffered terrible losses.</blockquote>

Meanwhile, Coenus circled around Porus’ rear and attacked his left flank from behind. Porus’ army fled straight into the waiting Craterus who had already crossed the river - 12,000 Indians and 80 elephants died to only 1,000 Macedonians.

Porus Captured & Aftermath

Throughout the battle King Porus remained on his elephant, despite suffering severe wounds, shocked to see his army flee but still reluctant to admit defeat and surrender. Alexander approached the proud, defeated king and asked him how he wanted to be treated - to which Porus responded that he wanted to be treated as a king. Alexander respected this and told Porus he would remain king, owing allegiance to Alexander. Plutarch wrote:

<blockquote>When Porus was taken prisoner, and Alexander asked him how he expected to be used, he answered, “As a king.’ For that expression, he said, when the same question was put to him a second time, comprehended everything. And Alexander, accordingly, not only suffered him to govern his own kingdom as satrap under himself, but gave him also the additional territory of various independent tribes whom he subdued…</blockquote>

From Hydaspes Alexander continued on towards the Indian Ocean. Sadly, this final march would be without his beloved Bucephalus. The great horse who he had been with him since his youth had died - reportedly either from old age (he was over thirty) or battle wounds. Alexander would build a city in his honor, Bucephalia. Unfortunately, Alexander's march to the ocean would not go without challenge. His army finally won their own battle with the king, convincing him to return home. About this decision Plutarch wrote, “Alexander at first was so grieved and enraged at his men’s reluctancy that he shut himself up in his tent and threw himself upon the ground…but at last the reasonable persuasions of his friends and the cries and lamentations of his soldiers…prevailed with him to think of returning.” Alexander would return to Babylon where he would die in 323 BCE. Following his death, his vast empire would be the scene of a series of Successor Wars for the next three decades.

Written by Donald L. Wasson, published on 26 February 2014 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms.